Oriel College on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Oriel College () is a constituent college of the

The college has nearly 40 fellows, about 300 undergraduates and some 250 graduates. Oriel was the last of Oxford's men's colleges to admit women in 1985, after more than six centuries as an all-male institution. Today, however, the student body has almost equal numbers of men and women. Oriel's notable alumni include two

Brome's foundation was confirmed in a charter dated 21 January 1326, in which the Crown, represented by the

Brome's foundation was confirmed in a charter dated 21 January 1326, in which the Crown, represented by the

Oxfordshire Architectural and Historical Society, Oxford

(

Oxfordshire Architectural and Historical Society, Oxford

(

'Medieval Oxford'

''A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 4: The City of Oxford'' (1979) — Oxford University Press via British History Online .

In 1643, a general obligation was imposed on Oxford colleges to support the Royalist cause in the

In 1643, a general obligation was imposed on Oxford colleges to support the Royalist cause in the  During the early 1720s, a constitutional struggle began between the provost and the fellows, culminating in a lawsuit. In 1721, Henry Edmunds was elected as a fellow by 9 votes to 3; his election was rejected by Provost George Carter, and on appeal, by the Visitor,

During the early 1720s, a constitutional struggle began between the provost and the fellows, culminating in a lawsuit. In 1721, Henry Edmunds was elected as a fellow by 9 votes to 3; his election was rejected by Provost George Carter, and on appeal, by the Visitor,

In the early 19th century, the reforming zeal of Provosts John Eveleigh and

In the early 19th century, the reforming zeal of Provosts John Eveleigh and

Oxfordshire Architectural and Historical Society, Oxford

(

The

The

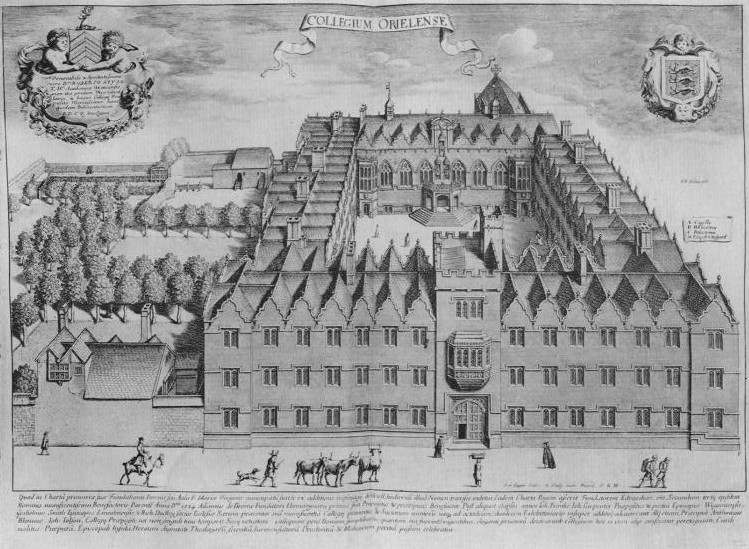

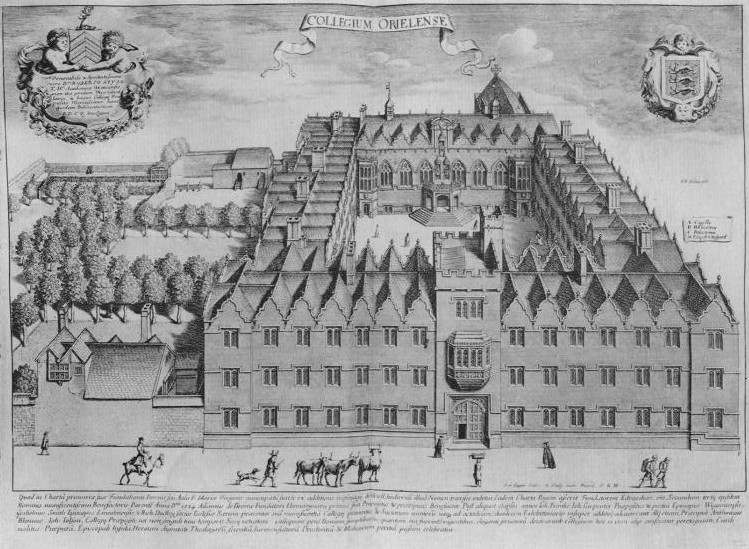

The current chapel is Oriel's third, the first being built around 1373 on the north side of First Quadrangle. By 1566, the chapel was located on the south side of the quadrangle, as shown in a drawing made for

The current chapel is Oriel's third, the first being built around 1373 on the north side of First Quadrangle. By 1566, the chapel was located on the south side of the quadrangle, as shown in a drawing made for

Originally a garden, the demand for more accommodation for undergraduates in the early 18th century resulted in two free-standing blocks being built. The first block erected was the Robinson Building on the east side, built in 1720 by Bishop Robinson at the suggestion of his wife, as the inscription over the door records. Its twin block, the Carter Building, was erected on the west side in 1729, as a result of a benefaction by Provost Carter. The two buildings stood for nearly a hundred years as detached blocks in the garden, and the architectural elements of First Quad are repeated on them — only here the seven gables are all alike. Between 1817 and 1819, they were joined up to First Quad with their present, rather incongruous connecting links. In the link to the Robinson Building, two purpose-built rooms have been incorporated – the Champneys Room, designed by Weldon Champneys, the nephew of

Originally a garden, the demand for more accommodation for undergraduates in the early 18th century resulted in two free-standing blocks being built. The first block erected was the Robinson Building on the east side, built in 1720 by Bishop Robinson at the suggestion of his wife, as the inscription over the door records. Its twin block, the Carter Building, was erected on the west side in 1729, as a result of a benefaction by Provost Carter. The two buildings stood for nearly a hundred years as detached blocks in the garden, and the architectural elements of First Quad are repeated on them — only here the seven gables are all alike. Between 1817 and 1819, they were joined up to First Quad with their present, rather incongruous connecting links. In the link to the Robinson Building, two purpose-built rooms have been incorporated – the Champneys Room, designed by Weldon Champneys, the nephew of  The north range houses the library and senior common rooms; designed in the Neoclassical style by

The north range houses the library and senior common rooms; designed in the Neoclassical style by

The Rhodes Building, pictured, was built in 1911 using £100,000 left to the college for that purpose by former student

The Rhodes Building, pictured, was built in 1911 using £100,000 left to the college for that purpose by former student

'Social and Cultural Activities'

''A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 4: The City of Oxford'' (1979) — Oxford University Press via British History Online . and after modernisation between 1991 and 1994, funded by Sir Philip and Lady Harris, contains accommodation, a seminar room and the college's main lecture theatre. The bronze plaque in the lobby commemorates his father, Captain Charles William Harris, after whom the building is named. The building was opened by

Bordered by the

Bordered by the

British History Online

. it includes the sports grounds for Oriel,

Local History Series: Medieval Hospitals

, Vale and Downland Museum, Wantage, UK. In 1649 the college rebuilt the main hospital range north of the chapel, destroyed in the Civil War, as a row of four

The college's

The college's

Accommodation is provided for all undergraduates, and for some graduates, though some accommodation is off-site. Members are generally expected to dine in hall, where there are two sittings every evening, Informal Hall and

Accommodation is provided for all undergraduates, and for some graduates, though some accommodation is off-site. Members are generally expected to dine in hall, where there are two sittings every evening, Informal Hall and

Oriel has produced many notable alumni, from statesmen and cricketers to industrialists; a notable undergraduate in the 16th century was

Oriel has produced many notable alumni, from statesmen and cricketers to industrialists; a notable undergraduate in the 16th century was

Oxford University News releases for journalists ''Oxford's Bodleian library holds a quarter of the world's Magna Cartas'' 9 November 2007

the engrossment (an official document from the Royal Chancery bearing the ruler's seal) dates from 1300.

Oriel JCR

— the undergraduate body of the college

Oriel MCR

— the graduate body of the college

Oriel College Boat Club

The Oriel Lions — Oriel College Drama Society

The Poor Print

– Student-run publication of Oriel College {{Use British English, date=February 2019 Colleges of the University of Oxford Educational institutions established in the 14th century 1324 establishments in England Grade I listed buildings in Oxford Grade I listed educational buildings Organisations based in Oxford with royal patronage Buildings and structures of the University of Oxford

University of Oxford

, mottoeng = The Lord is my light

, established =

, endowment = £6.1 billion (including colleges) (2019)

, budget = £2.145 billion (2019–20)

, chancellor ...

in Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

, England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

. Located in Oriel Square

Oriel Square, formerly known as Canterbury Square,Hibbert, Christopher, ''The Encyclopedia of Oxford''. London: Pan Macmillan, 1988, pp. 295–296. . is a square in central Oxford, England, located south of the High Street. The name was changed ...

, the college has the distinction of being the oldest royal foundation in Oxford (a title formerly claimed by University College

In a number of countries, a university college is a college institution that provides tertiary education but does not have full or independent university status. A university college is often part of a larger university. The precise usage varies ...

, whose claim of being founded by King Alfred

Alfred the Great (alt. Ælfred 848/849 – 26 October 899) was King of the West Saxons from 871 to 886, and King of the Anglo-Saxons from 886 until his death in 899. He was the youngest son of King Æthelwulf and his first wife Osburh, who bot ...

is no longer promoted). In recognition of this royal connection, the college has also been historically known as King's College and King's Hall.Watt, D. E. (editor), ''Oriel College, Oxford'' ( Trinity term, 1953) — Oxford University Archaeological Society, uses material collected by C. R. Jones, R. J. Brenato, D. K. Garnier, W. J. Frampton and N. Covington, under advice from W. A. Pantin, particularly in respect of the architecture and treasures (manuscripts, printed books and silver plate) sections. 16 page publication, produced in association with the Ashmolean Museum

The Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology () on Beaumont Street, Oxford, England, is Britain's first public museum. Its first building was erected in 1678–1683 to house the cabinet of curiosities that Elias Ashmole gave to the University of ...

as part of a college guide series. The reigning monarch of the United Kingdom (since 2022, Charles III

Charles III (Charles Philip Arthur George; born 14 November 1948) is King of the United Kingdom and the 14 other Commonwealth realms. He was the longest-serving heir apparent and Prince of Wales and, at age 73, became the oldest person to ...

) is the official visitor

A visitor, in English and Welsh law and history, is an overseer of an autonomous ecclesiastical or eleemosynary institution, often a charitable institution set up for the perpetual distribution of the founder's alms and bounty, who can interve ...

of the college.

The original medieval

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the Post-classical, post-classical period of World history (field), global history. It began with t ...

foundation established in 1324 by Adam de Brome

Adam de Brome (; died 16 June 1332) was an almoner to King Edward II and founder of Oriel College in Oxford, England. De Brome was probably the son of Thomas de Brome, taking his name from Brome near Eye in Suffolk; an inquisition held after ...

, under the patronage of King Edward II of England

Edward II (25 April 1284 – 21 September 1327), also called Edward of Caernarfon, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1307 until he was deposed in January 1327. The fourth son of Edward I, Edward became the heir apparent to ...

, was the House of the Blessed Mary at Oxford, and the college received a royal charter

A royal charter is a formal grant issued by a monarch under royal prerogative as letters patent. Historically, they have been used to promulgate public laws, the most famous example being the English Magna Carta (great charter) of 1215, bu ...

in 1326. In 1329, an additional royal grant of a manor house, La Oriole, eventually gave rise to its common name. The first design allowed for a provost and ten fellows, called "scholars", and the college remained a small body of graduate fellows until the 16th century, when it started to admit undergraduates. During the English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I ("Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of re ...

, Oriel played host to high-ranking members of the king's Oxford Parliament.

The main site of the college incorporates four medieval halls: Bedel Hall, St Mary Hall, St Martin Hall, and Tackley's Inn, the last being the oldest standing medieval hall in Oxford.Oriel College Memorandum (2003–04)The college has nearly 40 fellows, about 300 undergraduates and some 250 graduates. Oriel was the last of Oxford's men's colleges to admit women in 1985, after more than six centuries as an all-male institution. Today, however, the student body has almost equal numbers of men and women. Oriel's notable alumni include two

Nobel laureates

The Nobel Prizes ( sv, Nobelpriset, no, Nobelprisen) are awarded annually by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, the Swedish Academy, the Karolinska Institutet, and the Norwegian Nobel Committee to individuals and organizations who make ou ...

; prominent fellows have included founders of the Oxford Movement

The Oxford Movement was a movement of high church members of the Church of England which began in the 1830s and eventually developed into Anglo-Catholicism. The movement, whose original devotees were mostly associated with the University of O ...

. Among Oriel's more notable possessions are a painting by Bernard van Orley

Bernard van Orley (between 1487 and 1491 – 6 January 1541), also called Barend or Barent van Orley, Bernaert van Orley or Barend van Brussel, was a versatile Flemish artist and representative of Dutch and Flemish Renaissance painting, who w ...

and three pieces of medieval silver plate. , the college is ranked eighth in academic performance out of thirty colleges in the Norrington Table

The Norrington Table is an annual ranking of the colleges of the University of Oxford based on a score computed from the proportions of undergraduate students earning each of the various degree classifications based on that year's final examinati ...

.

History

Middle Ages

On 24 April 1324,Christopher and Edward Hibbert's ''The Encyclopedia of Oxford'' at p. 291 gives the date as 24 April, with the wording "Adam de Brome, obtained from King Edward II, licence".Jeremy Catto

Robert Jeremy Adam Inch Catto (27 July 1939 – 17 August 2018) was a British historian who was a Rhodes fellow and tutor in Modern History at Oriel College, Oxford, where he was also senior dean. Catto was a Brackenbury Scholar in History at ...

's article about Brome in the ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

The ''Dictionary of National Biography'' (''DNB'') is a standard work of reference on notable figures from British history, published since 1885. The updated ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (''ODNB'') was published on 23 September ...

'' gives the date as 20 April, with a similar wording. Rannie's ''Oriel College'' at p. 4 has "On April 28, 1324, Letters Patent

Letters patent ( la, litterae patentes) ( always in the plural) are a type of legal instrument in the form of a published written order issued by a monarch, president or other head of state, generally granting an office, right, monopoly, titl ...

issued by the King giving licence" the Rector of the University Church, Adam de Brome

Adam de Brome (; died 16 June 1332) was an almoner to King Edward II and founder of Oriel College in Oxford, England. De Brome was probably the son of Thomas de Brome, taking his name from Brome near Eye in Suffolk; an inquisition held after ...

, obtained a licence from King Edward II

Edward II (25 April 1284 – 21 September 1327), also called Edward of Caernarfon, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1307 until he was deposed in January 1327. The fourth son of Edward I, Edward became the heir apparent to the ...

to found a "certain college of scholars studying various disciplines in honour of the Virgin" and to endow it to the value of £30 a year. Hibbert, Christopher, ''The Encyclopedia of Oxford'' London: Macmillan

MacMillan, Macmillan, McMillen or McMillan may refer to:

People

* McMillan (surname)

* Clan MacMillan, a Highland Scottish clan

* Harold Macmillan, British statesman and politician

* James MacMillan, Scottish composer

* William Duncan MacMillan ...

(1988) pp. 291–295. Brome bought two properties in 1324, Tackley's Hall, on the south side of the High Street

High Street is a common street name for the primary business street of a city, town, or village, especially in the United Kingdom and Commonwealth. It implies that it is the focal point for business, especially shopping. It is also a metonym fo ...

, and Perilous Hall, on the north side of Broad Street, and as an investment, he also purchased the advowson

Advowson () or patronage is the right in English law of a patron (avowee) to present to the diocesan bishop (or in some cases the ordinary if not the same person) a nominee for appointment to a vacant ecclesiastical benefice or church living, ...

of a church in Aberford

Aberford is a village and civil parish on the eastern outskirts of the City of Leeds metropolitan borough in West Yorkshire, England. It had a population of 1,059 at the 2001 census, increasing to 1,180 at the 2011 Census. It is situated eas ...

.

Brome's foundation was confirmed in a charter dated 21 January 1326, in which the Crown, represented by the

Brome's foundation was confirmed in a charter dated 21 January 1326, in which the Crown, represented by the Lord Chancellor

The lord chancellor, formally the lord high chancellor of Great Britain, is the highest-ranking traditional minister among the Great Officers of State in Scotland and England in the United Kingdom, nominally outranking the prime minister. The ...

, was to exercise the rights of Visitor

A visitor, in English and Welsh law and history, is an overseer of an autonomous ecclesiastical or eleemosynary institution, often a charitable institution set up for the perpetual distribution of the founder's alms and bounty, who can interve ...

; a further charter drawn up in May of that year gave the rights of Visitor to Henry Burghersh

Henry Burghersh (1292 – 4 December 1340), was Bishop of Lincoln (1320-1340) and served as Lord Chancellor of England (1328–1330). He was a younger son of Robert de Burghersh, 1st Baron Burghersh (died 1306), and a nephew of Bartholomew de ...

, Bishop of Lincoln

The Bishop of Lincoln is the ordinary (diocesan bishop) of the Church of England Diocese of Lincoln in the Province of Canterbury.

The present diocese covers the county of Lincolnshire and the unitary authority areas of North Lincolnshire and ...

, as Oxford at that time was part of the diocese of Lincoln

The Diocese of Lincoln forms part of the Province of Canterbury in England. The present diocese covers the ceremonial county of Lincolnshire.

History

The diocese traces its roots in an unbroken line to the Pre-Reformation Diocese of Leices ...

. Under Edward's patronage, Brome diverted the revenues of the University Church to his college, which thereafter was responsible for appointing the Vicar and providing four chaplains to celebrate the daily services in the church. The college lost no time in seeking royal favour again after Edward II's deposition, and Edward III

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring r ...

confirmed his father's favour in February 1327, but the amended statutes with the Bishop of Lincoln

The Bishop of Lincoln is the ordinary (diocesan bishop) of the Church of England Diocese of Lincoln in the Province of Canterbury.

The present diocese covers the county of Lincolnshire and the unitary authority areas of North Lincolnshire and ...

as Visitor remained in force.

Varley, F.J., ''The Oriel College Lawsuit, 1724–26'Oxfordshire Architectural and Historical Society, Oxford

(

DOC

DOC, Doc, doc or DoC may refer to:

In film and television

* ''Doc'' (2001 TV series), a 2001–2004 PAX series

* ''Doc'' (1975 TV series), a 1975–1976 CBS sitcom

* "D.O.C." (''Lost''), a television episode

* ''Doc'' (film), a 1971 Wester ...

).

In 1329, the college received by royal grant a large house belonging to the Crown, known as La Oriole, on the site of what is now First Quad.

Pantin, W.A., ''Tackley's Inn'Oxfordshire Architectural and Historical Society, Oxford

(

DOC

DOC, Doc, doc or DoC may refer to:

In film and television

* ''Doc'' (2001 TV series), a 2001–2004 PAX series

* ''Doc'' (1975 TV series), a 1975–1976 CBS sitcom

* "D.O.C." (''Lost''), a television episode

* ''Doc'' (film), a 1971 Wester ...

).

It is from this property that the college acquired its common name, "Oriel"; the name was in use from about 1349. The word referred to an ''oratoriolum'', or oriel window

An oriel window is a form of bay window which protrudes from the main wall of a building but does not reach to the ground. Supported by corbels, bracket (architecture), brackets, or similar cantilevers, an oriel window is most commonly found pro ...

, forming a feature of the earlier property.

In the early 1410s several fellows of Oriel took part in the disturbances accompanying Archbishop Arundel's attempt to stamp out Lollardy

Lollardy, also known as Lollardism or the Lollard movement, was a proto-Protestant Christian religious movement that existed from the mid-14th century until the 16th-century English Reformation. It was initially led by John Wycliffe, a Catholic ...

in the university; the Lollard belief that religious power and authority came through piety

Piety is a virtue which may include religious devotion or spirituality. A common element in most conceptions of piety is a duty of respect. In a religious context piety may be expressed through pious activities or devotions, which may vary among ...

and not through the hierarchy of the Church particularly inflamed passions in Oxford, where its proponent, John Wycliffe

John Wycliffe (; also spelled Wyclif, Wickliffe, and other variants; 1328 – 31 December 1384) was an English scholastic philosopher, theologian, biblical translator, reformer, Catholic priest, and a seminary professor at the University of O ...

, had been head of Balliol. Disregarding the provost's authority, Oriel's fellows fought bloody battles with other scholars, killed one of the Chancellor

Chancellor ( la, cancellarius) is a title of various official positions in the governments of many nations. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the or lattice work screens of a basilica or law cou ...

's servants when they attacked his house, and were prominent among the group that obstructed the Archbishop and ridiculed his censures.

In 1442, Henry VI sanctioned an arrangement whereby the town was to pay the college £25 a year from the fee farm (a type of feudal tax) in exchange for decayed property, allegedly worth £30 a year, which the college could not afford to keep in repair. The arrangement was cancelled in 1450.Crossley, Alan (editor)'Medieval Oxford'

''A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 4: The City of Oxford'' (1979) — Oxford University Press via British History Online .

Early Modern

In 1643, a general obligation was imposed on Oxford colleges to support the Royalist cause in the

In 1643, a general obligation was imposed on Oxford colleges to support the Royalist cause in the English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I ("Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of re ...

. The King called for Oriel's plate, and almost all of it was given, the total weighing . of gilt, and . of "white" plate. In the same year the college was assessed at £1 of the weekly sum of £40 charged on the colleges and halls for the fortification of the city. When the Oxford Parliament was assembled during the Civil War in 1644, Oriel housed the executive committee of the Privy Council

A privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a state, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the mon ...

, Parliament being held at neighbouring Christ Church. Following the defeat of the Royalist cause, the university was scrutinised by the Parliamentarians, and five of the eighteen Oriel fellows were removed. The Visitors, on their own authority, elected fellows between 1648 and October 1652, when without reference to the Commissioners, John Washbourne was chosen; the autonomy of the college in this respect seems to have been restored.

In 1673 James Davenant, a fellow since 1661, complained to William Fuller, then Bishop of Lincoln, about Provost Say's conduct in the election of Thomas Twitty to a fellowship. Bishop Fuller appointed a commission that included the Vice-Chancellor

A chancellor is a leader of a college or university, usually either the executive or ceremonial head of the university or of a university campus within a university system.

In most Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth and former Commonwealth n ...

, Peter Mews

Peter Mews (25 March 1619 – 9 November 1706) was an English Royalist theologian and bishop. He was a captain captured at Naseby and he later had discussions in Scotland for the Royalist cause. Later made a Bishop he would report on non-confor ...

; the Dean of Christ Church, John Fell; and the Principal of Brasenose, Thomas Yates. On 1 August Fell reported to the Bishop that:

When this Devil of buying and selling is once cast out, your Lordship will, I hope, take care that he return not again, lest he bring seven worse than himself into the house after 'tis swept and garnisht.On 24 January 1674, Bishop Fuller issued a decree dealing with the recommendations of the commissioners—a majority of all the fellows should always be present at an election, so the provost could not push an election in a thin meeting, and fellows should be admitted immediately after their election. On 28 January Provost Say obtained from the King a recommendation for Twitty's election, but it was withdrawn on 13 February, following the Vice-Chancellor's refusal to swear Twitty into the university and the Bishop's protests at Court.

During the early 1720s, a constitutional struggle began between the provost and the fellows, culminating in a lawsuit. In 1721, Henry Edmunds was elected as a fellow by 9 votes to 3; his election was rejected by Provost George Carter, and on appeal, by the Visitor,

During the early 1720s, a constitutional struggle began between the provost and the fellows, culminating in a lawsuit. In 1721, Henry Edmunds was elected as a fellow by 9 votes to 3; his election was rejected by Provost George Carter, and on appeal, by the Visitor, Edmund Gibson

Edmund Gibson (16696 September 1748) was a British divine who served as Bishop of Lincoln and Bishop of London, jurist, and antiquary.

Early life and career

He was born in Bampton, Westmorland. In 1686 he was entered a scholar at Queen's Col ...

, then Bishop of Lincoln. The provost continued to reject candidates, fuelling discontent among the fellows, until a writ of attachment

A writ of attachment is a court order to " attach" or seize an asset. It is issued by a court to a law enforcement officer or sheriff. The writ of attachment is issued in order to satisfy a judgment issued by the court.

A prejudgment writ of att ...

against the Bishop of Lincoln was heard between 1724 and 1726. The opposing fellows, led by Edmunds, appealed to the original statutes, claiming the Crown as Visitor, making Gibson's decisions invalid; Provost Carter, supported by Bishop Gibson, appealed to the second version, claiming the Bishop of Lincoln as Visitor. The jury decided for the fellows, supporting the original charter of Edward II.

In a private printing of 1899, Provost Shadwell lists thirteen Gaudies observed by the college during the 18th century; by the end of the 19th century all but two, the Feast of the Immaculate Conception

The Solemnity of the Immaculate Conception, also called Immaculate Conception Day, celebrates the sinless lifespan and Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Virgin Mary on 8 December, nine months before the feast of the Nativity of Mary, celebrate ...

and the Purification of the Virgin

The Presentation of Jesus at the Temple (or ''in the temple'') is an early episode in the life of Jesus Christ, describing his presentation at the Temple in Jerusalem, that is celebrated by many churches 40 days after Christmas on Candlemas, ...

, had ceased to be celebrated.

Modern

In the early 19th century, the reforming zeal of Provosts John Eveleigh and

In the early 19th century, the reforming zeal of Provosts John Eveleigh and Edward Copleston

Edward Copleston (2 February 177614 October 1849) was an English churchman and academic, Provost of Oriel College, Oxford, from 1814 till 1828 and Bishop of Llandaff from 1827.

Life

Born into an ancient West Country family, Copleston was born ...

gained Oriel a reputation as the most brilliant college of the day. It was the centre of the " Oriel Noetics" — clerical liberals such as Richard Whately

Richard Whately (1 February 1787 – 8 October 1863) was an English academic, rhetorician, logician, philosopher, economist, and theologian who also served as a reforming Church of Ireland Archbishop of Dublin. He was a leading Broad Churchman ...

and Thomas Arnold

Thomas Arnold (13 June 1795 – 12 June 1842) was an English educator and historian. He was an early supporter of the Broad Church Anglican movement. As headmaster of Rugby School from 1828 to 1841, he introduced several reforms that were wide ...

were fellows,''Newman's Oxford – A Guide for Pilgrims'', Ecumenical undertaking between the Vicar of Littlemore and the Fathers of the Oratory at Birmingham — (Oxonian Rewley Press, c. 1978), p. 10 and during the 1830s, two intellectually eminent fellows of Oriel, John Keble

John Keble (25 April 1792 – 29 March 1866) was an English Anglican priest and poet who was one of the leaders of the Oxford Movement. Keble College, Oxford, was named after him.

Early life

Keble was born on 25 April 1792 in Fairford, Glouce ...

and Saint John Henry Newman, supported by Canon Pusey (also an Oriel fellow initially, later at Christ Church) and others, formed a group known as the Oxford Movement

The Oxford Movement was a movement of high church members of the Church of England which began in the 1830s and eventually developed into Anglo-Catholicism. The movement, whose original devotees were mostly associated with the University of O ...

, alternatively as the Tractarians, or familiarly as the Puseyites. The group was disgusted by the then Church of England and sought to revive the spirit of early Christianity

Early Christianity (up to the First Council of Nicaea in 325) spread from the Levant, across the Roman Empire, and beyond. Originally, this progression was closely connected to already established Jewish centers in the Holy Land and the Jewish ...

.

Ollard, S.L., ''The Oxford Architectural and Historical Society and the Oxford Movement'Oxfordshire Architectural and Historical Society, Oxford

(

DOC

DOC, Doc, doc or DoC may refer to:

In film and television

* ''Doc'' (2001 TV series), a 2001–2004 PAX series

* ''Doc'' (1975 TV series), a 1975–1976 CBS sitcom

* "D.O.C." (''Lost''), a television episode

* ''Doc'' (film), a 1971 Wester ...

)

Tension arose in college since Provost Edward Hawkins

Edward Hawkins (27 February 1789 – 18 November 1882) was an English churchman and academic, a long-serving Provost of Oriel College, Oxford known as a committed opponent of the Oxford Movement from its beginnings in his college.

Life

He was bor ...

was a determined opponent of the Movement.

During the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, a wall was built dividing Third Quad from Second Quad to accommodate members of Somerville College

Somerville College, a constituent college of the University of Oxford in England, was founded in 1879 as Somerville Hall, one of its first two women's colleges. Among its alumnae have been Margaret Thatcher, Indira Gandhi, Dorothy Hodgkin, ...

in St Mary's Hall while their college buildings were being used as a military hospital. At that time Oxford separated male and female students as far as possible; Vera Brittain

Vera Mary Brittain (29 December 1893 – 29 March 1970) was an English Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD) nurse, writer, feminist, socialist and pacifist. Her best-selling 1933 memoir '' Testament of Youth'' recounted her experiences during the Fir ...

, one of the Somerville students, recalled an amusing occurrence during her time there in her autobiography, ''Testament of Youth

''Testament of Youth'' is the first instalment, covering 1900–1925, in the memoir of Vera Brittain (1893–1970). It was published in 1933. Brittain's memoir continues with ''Testament of Experience'', published in 1957, and encompassing th ...

'':

In 1985, the college became the last all-male college in Oxford to start to admit women for matriculation

Matriculation is the formal process of entering a university, or of becoming eligible to enter by fulfilling certain academic requirements such as a matriculation examination.

Australia

In Australia, the term "matriculation" is seldom used now ...

as undergraduates. In 1984, the Senior Common Room voted 23–4 to admit women undergraduates from 1986. The Junior Common Room president believed that "the distinctive character of the college will be undermined".

A second feast day was added in 2007 by a benefaction from George Moody, formerly of Oriel, to be celebrated on or near St George's Day

Saint George's Day is the feast day of Saint George, celebrated by Christian churches, countries, and cities of which he is the patron saint, including Bulgaria, England, Georgia, Portugal, Romania, Cáceres, Alcoy, Aragon and Catalonia.

Sa ...

(23 April). The only remaining gaudy had then been Candlemas; the new annual dinner was to be known as the St. George's Day Gaudy. The dinner is black tie

Black tie is a semi-formal Western dress code for evening events, originating in British and American conventions for attire in the 19th century. In British English, the dress code is often referred to synecdochically by its principal element fo ...

and gowns, and by request of the benefactor, the main course will normally be goose.

Buildings and environs

First Quad (Front Quad)

The

The Oriel Street

Oriel may refer to:

Places Canada

* Oriel, a community in the municipality of Norwich, Ontario, Canada

Ireland

* Oriel Park, Dundalk, the home ground of Dundalk FC

* Oriel House, Ballincollig, County Cork

* Kingdom of Oriel ('' Airgíalla'' in I ...

site was acquired between 1329 and 1392. Nothing survives of the original buildings, La Oriole and the smaller St Martin's Hall in the south-east; both were demolished before the quadrangle was built in the artisan mannerist style during the 17th century. The south and west ranges and the gate tower were built around 1620 to 1622; the north and east ranges and the chapel buildings date from 1637 to 1642. The façade of the east range forms a classical E shape comprising the college chapel, hall and undercroft

An undercroft is traditionally a cellar or storage room, often brick-lined and vaulted, and used for storage in buildings since medieval times. In modern usage, an undercroft is generally a ground (street-level) area which is relatively open ...

. The exterior and interior of the ranges are topped by an alternating pattern of decorative gable

A gable is the generally triangular portion of a wall between the edges of intersecting roof pitches. The shape of the gable and how it is detailed depends on the structural system used, which reflects climate, material availability, and aesth ...

s. The gate house has a Perpendicular portal and canted Gothic

Gothic or Gothics may refer to:

People and languages

*Goths or Gothic people, the ethnonym of a group of East Germanic tribes

**Gothic language, an extinct East Germanic language spoken by the Goths

**Crimean Gothic, the Gothic language spoken b ...

oriel windows, with fan vaulting in the entrance. The room above has a particularly fine plaster ceiling and chimney piece of stucco

Stucco or render is a construction material made of aggregates, a binder, and water. Stucco is applied wet and hardens to a very dense solid. It is used as a decorative coating for walls and ceilings, exterior walls, and as a sculptural and a ...

caryatid

A caryatid ( or or ; grc, Καρυᾶτις, pl. ) is a sculpted female figure serving as an architectural support taking the place of a column or a pillar supporting an entablature on her head. The Greek term ''karyatides'' literally means "ma ...

s and panelling

Panelling (or paneling in the U.S.) is a millwork wall covering constructed from rigid or semi-rigid components. These are traditionally interlocking wood, but could be plastic or other materials.

Panelling was developed in antiquity to make roo ...

interlaced with studded bands sprouting into large flowers.

Hall

In the centre of the east range, theportico

A portico is a porch leading to the entrance of a building, or extended as a colonnade, with a roof structure over a walkway, supported by columns or enclosed by walls. This idea was widely used in ancient Greece and has influenced many cult ...

of the hall entrance commemorates its construction during the reign of Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

with the legend , 'Charles, being king', in capital letters in pierced stonework. The portico was completely rebuilt in 1897, and above it are statues of two kings: Edward II, the college's founder, on the left, and probably either Charles I or James I James I may refer to:

People

*James I of Aragon (1208–1276)

*James I of Sicily or James II of Aragon (1267–1327)

*James I, Count of La Marche (1319–1362), Count of Ponthieu

*James I, Count of Urgell (1321–1347)

*James I of Cyprus (1334–13 ...

, although this is disputed; above those is a statue of the Blessed Virgin Mary

Mary; arc, ܡܪܝܡ, translit=Mariam; ar, مريم, translit=Maryam; grc, Μαρία, translit=María; la, Maria; cop, Ⲙⲁⲣⲓⲁ, translit=Maria was a first-century Jews, Jewish woman of Nazareth, the wife of Saint Joseph, Jose ...

, after whom the college is officially named. The top breaks the Jacobean tradition and has classical pilaster

In classical architecture

Classical architecture usually denotes architecture which is more or less consciously derived from the principles of Greek and Roman architecture of classical antiquity, or sometimes even more specifically, from the ...

s, a shield with garlands, and a segmental pediment

Pediments are gables, usually of a triangular shape.

Pediments are placed above the horizontal structure of the lintel, or entablature, if supported by columns. Pediments can contain an overdoor and are usually topped by hood moulds.

A pedimen ...

.

The hall has a hammerbeam roof

A hammerbeam roof is a decorative, open timber roof truss typical of English Gothic architecture and has been called "...the most spectacular endeavour of the English Medieval carpenter". They are traditionally timber framed, using short beams pr ...

and a louvre in the centre, which was originally the means of escape for smoke rising from a fireplace in the centre of the floor. The wooden panelling was designed by Ninian Comper

Sir John Ninian Comper (10 June 1864 – 22 December 1960) was a Scottish architect; one of the last of the great Gothic Revival architects.

His work almost entirely focused on the design, restoration and embellishment of churches, and the des ...

and was erected in 1911 in place of some previous 19th-century Gothic type, though even earlier panelling, dating from 1710, is evident in the buttery.

Behind the high table is a portrait of Edward II; underneath is a longsword

A longsword (also spelled as long sword or long-sword) is a type of European sword characterized as having a cruciform hilt with a grip for primarily two-handed use (around ), a straight double-edged blade of around , and weighing approximatel ...

brought to the college in 1902 after being preserved for many years on one of the college's estates at Swainswick, near Bath. On either side are portraits of Sir Walter Raleigh

Sir Walter Raleigh (; – 29 October 1618) was an English statesman, soldier, writer and explorer. One of the most notable figures of the Elizabethan era, he played a leading part in English colonisation of North America, suppressed rebellion ...

and Joseph Butler

Joseph Butler (18 May O.S. 1692 – 16 June O.S. 1752) was an English Anglican bishop, theologian, apologist, and philosopher, born in Wantage in the English county of Berkshire (now in Oxfordshire). He is known for critiques of Deism, Thom ...

. The other portraits around the hall include other prominent members of Oriel such as Matthew Arnold

Matthew Arnold (24 December 1822 – 15 April 1888) was an English poet and cultural critic who worked as an inspector of schools. He was the son of Thomas Arnold, the celebrated headmaster of Rugby School, and brother to both Tom Arnold, lite ...

, Thomas Arnold

Thomas Arnold (13 June 1795 – 12 June 1842) was an English educator and historian. He was an early supporter of the Broad Church Anglican movement. As headmaster of Rugby School from 1828 to 1841, he introduced several reforms that were wide ...

, James Anthony Froude

James Anthony Froude ( ; 23 April 1818 – 20 October 1894) was an English historian, novelist, biographer, and editor of ''Fraser's Magazine''. From his upbringing amidst the Anglo-Catholic Oxford Movement, Froude intended to become a clergy ...

, John Keble

John Keble (25 April 1792 – 29 March 1866) was an English Anglican priest and poet who was one of the leaders of the Oxford Movement. Keble College, Oxford, was named after him.

Early life

Keble was born on 25 April 1792 in Fairford, Glouce ...

, John Henry Newman

John Henry Newman (21 February 1801 – 11 August 1890) was an English theologian, academic, intellectual, philosopher, polymath, historian, writer, scholar and poet, first as an Anglican ministry, Anglican priest and later as a Catholi ...

, Richard Whately

Richard Whately (1 February 1787 – 8 October 1863) was an English academic, rhetorician, logician, philosopher, economist, and theologian who also served as a reforming Church of Ireland Archbishop of Dublin. He was a leading Broad Churchman ...

and John Robinson. In 2002, the college commissioned one of the largest portraits of Queen Elizabeth II, measuring , from Jeff Stultiens to hang in the hall; the painting was unveiled the following year.

The stained glass

Stained glass is coloured glass as a material or works created from it. Throughout its thousand-year history, the term has been applied almost exclusively to the windows of churches and other significant religious buildings. Although tradition ...

in the windows display the coats of arms

A coat of arms is a heraldic visual design on an escutcheon (i.e., shield), surcoat, or tabard (the latter two being outer garments). The coat of arms on an escutcheon forms the central element of the full heraldic achievement, which in its wh ...

of benefactors and distinguished members of the college; three of the windows were designed by Ninian Comper. The window next to the entrance on the east side contains the arms of Regius Professors of Modern History who have been ''ex officio

An ''ex officio'' member is a member of a body (notably a board, committee, council) who is part of it by virtue of holding another office. The term '' ex officio'' is Latin, meaning literally 'from the office', and the sense intended is 'by right ...

'' fellows of the college.

Chapel

The current chapel is Oriel's third, the first being built around 1373 on the north side of First Quadrangle. By 1566, the chapel was located on the south side of the quadrangle, as shown in a drawing made for

The current chapel is Oriel's third, the first being built around 1373 on the north side of First Quadrangle. By 1566, the chapel was located on the south side of the quadrangle, as shown in a drawing made for Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen".

El ...

's visit to Oxford in that year. The present building was consecrated in 1642 and despite subsequent restorations it largely retains its original appearance.

The bronze lectern

A lectern is a reading desk with a slanted top, on which documents or books are placed as support for reading aloud, as in a scripture reading, lecture, or sermon. A lectern is usually attached to a stand or affixed to some other form of support. ...

was given to the college in 1654. The black and white marble paving dates from 1677 to 1678. Except for the pew

A pew () is a long bench (furniture), bench seat or enclosed box, used for seating Member (local church), members of a Church (congregation), congregation or choir in a Church (building), church, synagogue or sometimes a courtroom.

Overview

...

s on the west, dating from 1884, the panelling, stalls and screens are all 17th-century, as are the altar and carved communion rails

The altar rail (also known as a communion rail or chancel rail) is a low barrier, sometimes ornate and usually made of stone, wood or metal in some combination, delimiting the chancel or the sanctuary and altar in a church, from the nave and oth ...

. Behind the altar is the oil-on-panel painting ''The Carrying of the Cross'', also titled ''Christ Falls, with the Cross, before a City Gate'', by the Flemish Renaissance

The Renaissance in the Low Countries was a cultural period in the Northern Renaissance that took place in around the 16th century in the Low Countries (corresponding to modern-day Belgium, the Netherlands and French Flanders).

Culture in the Low C ...

painter Bernard van Orley

Bernard van Orley (between 1487 and 1491 – 6 January 1541), also called Barend or Barent van Orley, Bernaert van Orley or Barend van Brussel, was a versatile Flemish artist and representative of Dutch and Flemish Renaissance painting, who w ...

. A companion piece to the painting is in the National Gallery of Scotland

The Scottish National Gallery (formerly the National Gallery of Scotland) is the national art gallery of Scotland. It is located on The Mound in central Edinburgh, close to Princes Street. The building was designed in a neoclassical style by W ...

. The organ case dates from 1716; originally designed by Christopher Schreider for St Mary Abbots

St Mary Abbots is a church located on Kensington High Street and the corner of Kensington Church Street in London W8.

The present church structure was built in 1872 to the designs of Sir George Gilbert Scott, who combined neo-Gothic and early ...

Church, Kensington, it was acquired by Oriel in 1884.

Above the entrance to the chapel is an oriel that, until the 1880s, was a room on the first floor that formed part of a set of rooms that were occupied by Richard Whately

Richard Whately (1 February 1787 – 8 October 1863) was an English academic, rhetorician, logician, philosopher, economist, and theologian who also served as a reforming Church of Ireland Archbishop of Dublin. He was a leading Broad Churchman ...

, and later by Saint John Henry Newman. Whately is said to have used the space as a larder and Newman is said to have used it for his private prayers – when the organ was installed in 1884, the space was used for the blower. The wall that once separated the room from the ante-chapel

The ante-chapel is that portion of a chapel which lies on the western side of the choir screen.

In some of the colleges at Oxford and Cambridge the ante-chapel is carried north and south across the west end of the chapel, constituting a western ...

was removed, making it accessible from the chapel. The organ was built by J. W. Walker & Sons in 1988; in 1991 the space behind the organ was rebuilt as an oratory and memorial to Newman and the Oxford Movement

The Oxford Movement was a movement of high church members of the Church of England which began in the 1830s and eventually developed into Anglo-Catholicism. The movement, whose original devotees were mostly associated with the University of O ...

. A new stained-glass window designed by Vivienne Haig and realised by Douglas Hogg was completed and installed in 2001.

During the late 1980s, the chapel was extensively restored with the assistance of donations from Lady Norma Dalrymple-Champneys. During this work, the chandelier, given in 1885 by Provost Shadwell while still a fellow, was put back in place, the organ was restored, the painting mounted behind the altar, and the chapel repainted. A list of former chaplains and organ scholars was erected in the ante-chapel.

Second Quad (Back Quad)

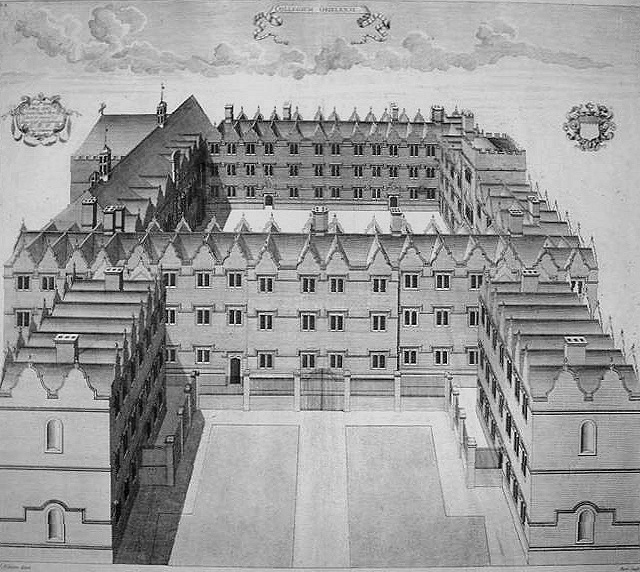

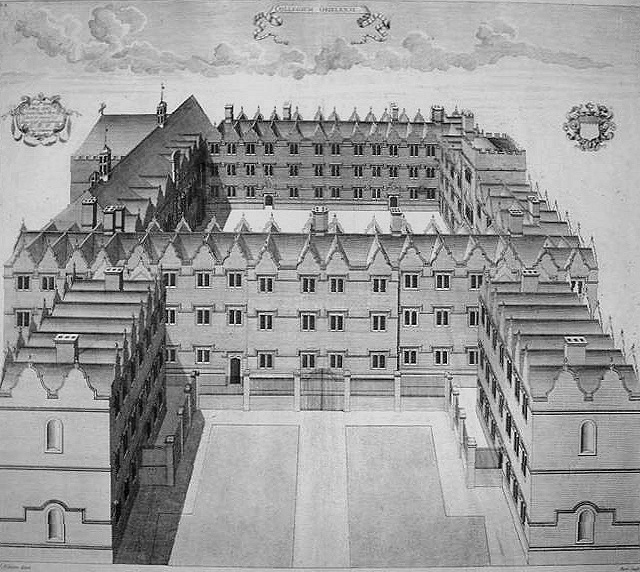

Originally a garden, the demand for more accommodation for undergraduates in the early 18th century resulted in two free-standing blocks being built. The first block erected was the Robinson Building on the east side, built in 1720 by Bishop Robinson at the suggestion of his wife, as the inscription over the door records. Its twin block, the Carter Building, was erected on the west side in 1729, as a result of a benefaction by Provost Carter. The two buildings stood for nearly a hundred years as detached blocks in the garden, and the architectural elements of First Quad are repeated on them — only here the seven gables are all alike. Between 1817 and 1819, they were joined up to First Quad with their present, rather incongruous connecting links. In the link to the Robinson Building, two purpose-built rooms have been incorporated – the Champneys Room, designed by Weldon Champneys, the nephew of

Originally a garden, the demand for more accommodation for undergraduates in the early 18th century resulted in two free-standing blocks being built. The first block erected was the Robinson Building on the east side, built in 1720 by Bishop Robinson at the suggestion of his wife, as the inscription over the door records. Its twin block, the Carter Building, was erected on the west side in 1729, as a result of a benefaction by Provost Carter. The two buildings stood for nearly a hundred years as detached blocks in the garden, and the architectural elements of First Quad are repeated on them — only here the seven gables are all alike. Between 1817 and 1819, they were joined up to First Quad with their present, rather incongruous connecting links. In the link to the Robinson Building, two purpose-built rooms have been incorporated – the Champneys Room, designed by Weldon Champneys, the nephew of Basil Champneys

Basil Champneys (17 September 1842 – 5 April 1935) was an English architect and author whose most notable buildings include Manchester's John Rylands Library, Somerville College Library (Oxford), Newnham College, Cambridge, Lady Margaret Hall, ...

, and the Benefactors Room, a panelled room honouring benefactors of the college. A Gothic oriel window, belonging to the provost's lodgings, was added to the Carter Building in 1826.

The north range houses the library and senior common rooms; designed in the Neoclassical style by

The north range houses the library and senior common rooms; designed in the Neoclassical style by James Wyatt

James Wyatt (3 August 1746 – 4 September 1813) was an English architect, a rival of Robert Adam in the neoclassical and neo-Gothic styles. He was elected to the Royal Academy in 1785 and was its president from 1805 to 1806.

Early life

W ...

, it was built between 1788 and 1796 to accommodate the books requested by Edward, Baron Leigh, formerly High Steward of the university and an Orielensis, whose gift had doubled the size of the library. The two-storey building has rusticated arches on the ground floor and a row of Ionic columns above, dividing the façade into seven bays — the ground floor contains the first purpose-built senior common rooms in Oxford, above is the library.

On 7 March 1949, a fire spread from the library roof; over 300 printed books and the manuscripts on exhibition were completely destroyed, and over 3,000 books needed repair, though the main structure suffered little damage and restoration took less than a year.

Third Quad (St Mary's Quad)

The south, east and west ranges of Third Quadrangle contain elements of St Mary Hall, which was incorporated into Oriel in 1902; less than a decade later, the Hall's buildings on the northern side were demolished for the construction of the Rhodes Building. Bedel Hall in the south was formally amalgamated with St Mary Hall in 1505. In the south range, parts of the medieval buildings survive and are incorporated into staircase ten — the straight, steep flight of stairs and timber-framed partitions date from a mid-15th century rebuilding of St Mary Hall. The former Chapel, Hall and Buttery of St Mary Hall, built in 1640, form part of the Junior Library and Junior Common Room. Viewed from Third Quad, the chapel, with its Gothic windows, can be seen to have been built neatly on top of the Hall, a unique example in Oxford of such a plan. On the east side of the quad is a simple rustic style timber-frame building; known as "the Dolls' House", it was erected by Principal King in 1743. In 1826 an ornate range was erected by St Mary Hall in theGothic Revival

Gothic Revival (also referred to as Victorian Gothic, neo-Gothic, or Gothick) is an architectural movement that began in the late 1740s in England. The movement gained momentum and expanded in the first half of the 19th century, as increasingly ...

style, incorporating the old gate of St Mary Hall, on the west side of the quad. Designed by Daniel Robertson, it contains two quite ornate oriels placed asymmetrically, one is of six lights, the other four. They are the best example of the pre-archaeological Gothic in Oxford. The large oriel on the first floor at the north end was once the drawing room window of the Principal of the Hall. Parts of the street wall incorporated into this range show traces of blocked windows dating from the same period of rebuilding in the 15th century as the present-day staircase ten.

Cecil Rhodes

Cecil John Rhodes (5 July 1853 – 26 March 1902) was a British mining magnate and politician in southern Africa who served as Prime Minister of the Cape Colony from 1890 to 1896.

An ardent believer in British imperialism, Rhodes and his Br ...

. It was designed by Basil Champneys

Basil Champneys (17 September 1842 – 5 April 1935) was an English architect and author whose most notable buildings include Manchester's John Rylands Library, Somerville College Library (Oxford), Newnham College, Cambridge, Lady Margaret Hall, ...

and stands on the site of the house of the St Mary Hall Principal, on the High Street. Champneys's first proposal for the building included an open arcade

Arcade most often refers to:

* Arcade game, a coin-operated game machine

** Arcade cabinet, housing which holds an arcade game's hardware

** Arcade system board, a standardized printed circuit board

* Amusement arcade, a place with arcade games

* ...

to the High Street, a dome

A dome () is an architectural element similar to the hollow upper half of a sphere. There is significant overlap with the term cupola, which may also refer to a dome or a structure on top of a dome. The precise definition of a dome has been a m ...

d central feature and balustraded

A baluster is an upright support, often a vertical moulded shaft, square, or lathe-turned form found in stairways, parapets, and other architectural features. In furniture construction it is known as a spindle. Common materials used in its con ...

parapet

A parapet is a barrier that is an extension of the wall at the edge of a roof, terrace, balcony, walkway or other structure. The word comes ultimately from the Italian ''parapetto'' (''parare'' 'to cover/defend' and ''petto'' 'chest/breast'). Whe ...

. The left hand block and much of the centre was to be given up to a new provost's lodging, and the five windows on the first floor above the arcade were to light a gallery belonging to the lodging. The college eventually decided to retain the existing provost's lodging and demanded detailing "more in accordance with the style which has become traditional in Oxford". It became the last building of the Jacobean revival style in Oxford.

The staircases of the interior façade are decorated with cartouches similar to those found in First Quad, and likewise bear the arms of important figures in the college's history; (13) Sir Walter Raleigh who was an undergraduate from 1572 to 1574, (14) John Keble who was a fellow between 1811 and 1835, (archway) Edward Hawkins who was provost from 1828 until 1882 and (15) Gilbert White who was an undergraduate from 1739 until 1743 and a fellow from 1744 until 1793.

The building was not entirely well received; William Sherwood, Mayor of Oxford and Master of Magdalen College School, wrote: "Oriel asbroken out into the High, ... destroying a most picturesque group of old houses in so doing, and, to put it gently, hardly compensating us for their removal."

Rhodes statue

On the side facing the High Street, there is a statue of Rhodes over the main entrance, withEdward VII

Edward VII (Albert Edward; 9 November 1841 – 6 May 1910) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and Emperor of India, from 22 January 1901 until his death in 1910.

The second child and eldest son of Queen Victoria an ...

and George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until Death and state funeral of George V, his death in 1936.

Born duri ...

beneath. These formed part of a group of seven statues commissioned for the building from the sculptor Henry Pegram

Henry Alfred Pegram (27 July 1862 – 26 March 1937) was a British sculptor and exponent of the New Sculpture movement.Chamot, M.; Farr, D.; Butlin, M.: The Modern British Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture'' London 1964.

Life

Pegram w ...

. The inscription reads: "", which, as well as acknowledging Rhodes's munificence, is a chronogram

A chronogram is a sentence or inscription in which specific letters, interpreted as numerals (such as Roman numerals), stand for a particular date when rearranged. The word, meaning "time writing", derives from the Greek words ''chronos'' (χ ...

giving the date of construction, 1911.

The statue has been the subject of protests for several years in the wake of the Rhodes Must Fall

Rhodes Must Fall was a protest movement that began on 9 March 2015, originally directed against a statue at the University of Cape Town (UCT) that commemorates Cecil Rhodes. The campaign for the statue's removal received global attention and ...

movement in 2015. Hundreds of protestors again demanded its removal in June 2020, in the wake of the removal of the statue of Edward Colston

The statue of Edward Colston is a bronze statue of Bristol-born merchant and trans-Atlantic slave trader, Edward Colston (1636–1721). It was created in 1895 by the Irish sculptor John Cassidy and was formerly erected on a plinth of Portland ...

in Bristol a few days previously. The statues had been targeted during the protests that arose following the murder of George Floyd

On , George Floyd, a 46-year-old black man, was murdered in the U.S. city of Minneapolis by Derek Chauvin, a 44-year-old white police officer. Floyd had been arrested on suspicion of using a counterfeit $20 bill. Chauvin knelt on Floyd's n ...

in the United States. On 20 May 2021, however, the college decided not to remove the statue despite the majority of members of a commission to decide its future recommending removal; Oriel College cited costs and 'complex' planning procedures. Roughly 150 Oxford lecturers stated they will not teach Oriel students more than is required in their contracts in protest at the decision to keep the statue.

Island Site (O'Brien Quad)

This is a convex quadrilateral of buildings, bordered by theHigh Street

High Street is a common street name for the primary business street of a city, town, or village, especially in the United Kingdom and Commonwealth. It implies that it is the focal point for business, especially shopping. It is also a metonym fo ...

, and the meeting of Oriel Street

Oriel may refer to:

Places Canada

* Oriel, a community in the municipality of Norwich, Ontario, Canada

Ireland

* Oriel Park, Dundalk, the home ground of Dundalk FC

* Oriel House, Ballincollig, County Cork

* Kingdom of Oriel ('' Airgíalla'' in I ...

and King Edward Street

King Edward Street is a street running between the High Street to the north and Oriel Square to the south in central Oxford, England.

To the east is the "Island" site of Oriel College, one of the colleges of Oxford University. To the west ...

in Oriel Square

Oriel Square, formerly known as Canterbury Square,Hibbert, Christopher, ''The Encyclopedia of Oxford''. London: Pan Macmillan, 1988, pp. 295–296. . is a square in central Oxford, England, located south of the High Street. The name was changed ...

. The site took six hundred years to acquire and although it contains teaching rooms and the Harris Lecture Theatre, it is largely given over to accommodation.

On the High Street

High Street is a common street name for the primary business street of a city, town, or village, especially in the United Kingdom and Commonwealth. It implies that it is the focal point for business, especially shopping. It is also a metonym fo ...

, No. 106 and 107 stand on the site of Tackley's Inn; built around 1295, it was the first piece of property that Adam de Brome acquired when he began to found the college in 1324. It comprised a hall and chambers leased to scholars, behind a frontage of five shops, with the scholars above and a cellar of five bays below. The hall, which was open to the roof, was 33 feet (10 m) long, 20 feet (6 m) wide, and about 22 feet (7 m) high; at the east end was a large chamber with another chamber above it. The south wall of the building, which survives, was partly of stone and contains a large two-light early 14th-century window. The cellar below is of the same date and is the best preserved medieval cellar in Oxford; originally entered by stone steps from the street, it has a stone vault

Vault may refer to:

* Jumping, the act of propelling oneself upwards

Architecture

* Vault (architecture), an arched form above an enclosed space

* Bank vault, a reinforced room or compartment where valuables are stored

* Burial vault (enclosure ...

divided into four sections by two diagonal ribs, with carved corbel

In architecture, a corbel is a structural piece of stone, wood or metal jutting from a wall to carry a superincumbent weight, a type of bracket. A corbel is a solid piece of material in the wall, whereas a console is a piece applied to the s ...

s.

No. 12 Oriel Street, now staircases 19 and 20, is the oldest tenement acquired by the college; known as Kylyngworth's, it was granted to the college in 1392 by Thomas de Lentwardyn, fellow and later provost, having previously been let to William de Daventre, Oriel's fourth provost, in 1367. A back wing to the property was added around 1600 and further work to the front was conducted in 1724–1738. In 1985, funded by a gift from Edgar O'Brien and £10,000 from the Pilgrim Trust

The Pilgrim Trust is a national grant-making trust in the United Kingdom. It is based in London and is a registered charity under English law.

It was founded in 1930 with a two million pound grant by Edward Harkness, an American philanthropist. T ...

, Kylyngworth's was refurbished along with Nos. 10, 9 and 7.

King Edward Street

King Edward Street is a street running between the High Street to the north and Oriel Square to the south in central Oxford, England.

To the east is the "Island" site of Oriel College, one of the colleges of Oxford University. To the west ...

was created by the college between 1872 and 1873 when 109 and 110 High Street were demolished. The old shops on each side of the road were pulled down and rebuilt, and to preserve the continuity, the new shops were numbered 108 and 109–112. Named after the college's founder, the road was opened in 1873. On the wall of the first floor of No. 6, there is a large metal plaque with a portrait of Cecil Rhodes; underneath is the inscription:

In this house, the Rt. Hon Cecil John Rhodes kept academical residence in the year 1881. This memorial is erected by Alfred Mosely in recognition of the great services rendered by Cecil Rhodes to his country.In the centre of the quad is the Harris Building, formerly Oriel court, a

real tennis

Real tennis – one of several games sometimes called "the sport of kings" – is the original racquet sport from which the modern game of tennis (also called "lawn tennis") is derived. It is also known as court tennis in the United Sta ...

court where Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

played tennis with his nephew Prince Rupert

Prince Rupert of the Rhine, Duke of Cumberland, (17 December 1619 (O.S.) / 27 December (N.S.) – 29 November 1682 (O.S.)) was an English army officer, admiral, scientist and colonial governor. He first came to prominence as a Royalist cavalr ...

in December 1642 and King Edward VII

Edward VII (Albert Edward; 9 November 1841 – 6 May 1910) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and Emperor of India, from 22 January 1901 until his death in 1910.

The second child and eldest son of Queen Victoria a ...

had his first tennis lesson in 1859. The building was in use as a lecture hall by 1923,Crossley, Alan (editor)'Social and Cultural Activities'

''A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 4: The City of Oxford'' (1979) — Oxford University Press via British History Online . and after modernisation between 1991 and 1994, funded by Sir Philip and Lady Harris, contains accommodation, a seminar room and the college's main lecture theatre. The bronze plaque in the lobby commemorates his father, Captain Charles William Harris, after whom the building is named. The building was opened by

John Major

Sir John Major (born 29 March 1943) is a British former politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from 1990 to 1997, and as Member of Parliament ...

, then Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is not ...

, on 10 August 1993.

Rectory Road

Cowley Road

__NOTOC__

Cowley Road is an arterial road in the city of Oxford, England, running southeast from near the city centre at The Plain near Magdalen Bridge, through the inner city area of East Oxford, and to the industrial suburb of Cowley. The ...

, this site was formerly Nazareth House, a residential care home convent

A convent is a community of monks, nuns, religious brothers or, sisters or priests. Alternatively, ''convent'' means the building used by the community. The word is particularly used in the Catholic Church, Lutheran churches, and the Anglican ...

— Goldie Wing (shown left) and Larmenier House are its surviving buildings. Nazareth House itself was demolished to make room for two purpose-built halls of residence, James Mellon Hall (shown right) and David Paterson House. The two new halls were opened by Queen Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 1926 – 8 September 2022) was Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 6 February 1952 until Death and state funeral of Elizabeth II, her death in 2022. She was queen ...

on 8 November 2000.

As it is about ten minutes' walk from college and more peaceful than the middle of the city, it has become the principal choice of accommodation for Oriel's graduates and finalists. The site has its own common rooms, squash

Squash may refer to:

Sports

* Squash (sport), the high-speed racquet sport also known as squash racquets

* Squash (professional wrestling), an extremely one-sided match in professional wrestling

* Squash tennis, a game similar to squash but pla ...

court, gymnasium and support staff.

Bartlemas

Bartlemas is a conservation area that incorporates the remaining buildings of aleper

Leprosy, also known as Hansen's disease (HD), is a long-term infection by the bacteria ''Mycobacterium leprae'' or ''Mycobacterium lepromatosis''. Infection can lead to damage of the nerves, respiratory tract, skin, and eyes. This nerve damage ...

hospital founded by Henry I Henry I may refer to:

876–1366

* Henry I the Fowler, King of Germany (876–936)

* Henry I, Duke of Bavaria (died 955)

* Henry I of Austria, Margrave of Austria (died 1018)

* Henry I of France (1008–1060)

* Henry I the Long, Margrave of the ...

;Page, William (editor), 'Hospitals: St Bartholomew, Oxford', ''A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 2'' (1907), pp. 157–58 has 1326 to de Brome and 1328 to Oriel — published by Oxford University PresBritish History Online

. it includes the sports grounds for Oriel,

Jesus

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religious ...

and Lincoln

Lincoln most commonly refers to:

* Abraham Lincoln (1809–1865), the sixteenth president of the United States

* Lincoln, England, cathedral city and county town of Lincolnshire, England

* Lincoln, Nebraska, the capital of Nebraska, U.S.

* Lincol ...

Colleges, along with landscaping for wildlife and small scale urban development.

In 1326 Provost Adam de Brome was appointed warden of St Bartholomew's; a leper hospital in Cowley Marsh, the hospital was later granted to the college by Edward III

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring r ...

, along with the payments it had been receiving from the fee farm. It was increasingly used as a rest house for sick members of the college needing a change of air.

Markham, Margaret, ''Medieval Hospitals'' has grant date as 132Local History Series: Medieval Hospitals

, Vale and Downland Museum, Wantage, UK. In 1649 the college rebuilt the main hospital range north of the chapel, destroyed in the Civil War, as a row of four

almshouse

An almshouse (also known as a bede-house, poorhouse, or hospital) was charitable housing provided to people in a particular community, especially during the medieval era. They were often targeted at the poor of a locality, at those from certain ...

s, called Bartlemas House. Bartlemas Chapel and two farm cottages are the other extant buildings.

Filming location

The buildings of Oriel College were used as a location forHugh Grant

Hugh John Mungo Grant (born 9 September 1960) is an English actor. He established himself early in his career as both a charming, and vulnerable romantic lead and has since transitioned into a dramatic character actor. Among his numerous a ...

's first film, '' Privileged'' (1982), as well as ''Oxford Blues

''Oxford Blues'' is a 1984 British comedy-drama sports film written and directed by Robert Boris and starring Rob Lowe, Ally Sheedy and Amanda Pays. It is a remake of the 1938 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer film ''A Yank at Oxford'' and was Lowe's first ...

'' (1984), '' True Blue'' (1991) and ''The Dinosaur Hunter'' (2000).Leonard, Bill, ''The Oxford of Inspector Morse'' Location Guides, Oxford (2004) pp.100 and 176 . The television crime series ''Inspector Morse

Detective Chief Inspector Endeavour Morse, GM, is the eponymous fictional character in the series of detective novels by British author Colin Dexter. On television, he appears in the 33-episode drama series '' Inspector Morse'' (1987–2000), ...

'' used the college in the episodes "Ghost in the Machine" (under the name of "Courtenay College"), "The Silent World of Nicholas Quinn", "The Infernal Serpent", "Deadly Slumber", "Twilight of the Gods" and "Death is now My Neighbour", and in the one-off follow on, ''Lewis

Lewis may refer to:

Names

* Lewis (given name), including a list of people with the given name

* Lewis (surname), including a list of people with the surname

Music

* Lewis (musician), Canadian singer

* "Lewis (Mistreated)", a song by Radiohead ...

'', the Middle Common Room and Oriel Square were used.

Heraldry

The college's

The college's coat of arms

A coat of arms is a heraldry, heraldic communication design, visual design on an escutcheon (heraldry), escutcheon (i.e., shield), surcoat, or tabard (the latter two being outer garments). The coat of arms on an escutcheon forms the central ele ...

are blazon

In heraldry and heraldic vexillology, a blazon is a formal description of a coat of arms, flag or similar emblem, from which the reader can reconstruct the appropriate image. The verb ''to blazon'' means to create such a description. The vis ...

ed: "Gules

In heraldry, gules () is the tincture with the colour red. It is one of the class of five dark tinctures called "colours", the others being azure (blue), sable (black), vert (green) and purpure (purple).

In engraving, it is sometimes depict ...

, three lions passant guardant or within a bordure

In heraldry, a bordure is a band of contrasting tincture forming a border around the edge of a shield, traditionally one-sixth as wide as the shield itself. It is sometimes reckoned as an ordinary and sometimes as a subordinary.

A bordure encl ...

engrailed argent

In heraldry, argent () is the tincture of silver, and belongs to the class of light tinctures called "metals". It is very frequently depicted as white and usually considered interchangeable with it. In engravings and line drawings, regions to b ...

". In recognition of Oriel's foundation by King Edward II, the arms are based on the royal arms of England

The royal arms of England are the Coat of arms, arms first adopted in a fixed form at the start of the age of heraldry (circa 1200) as Armorial of the House of Plantagenet, personal arms by the House of Plantagenet, Plantagenet kings who ruled ...

, which also feature three lions

The lion (''Panthera leo'') is a large cat of the genus '' Panthera'' native to Africa and India. It has a muscular, broad-chested body; short, rounded head; round ears; and a hairy tuft at the end of its tail. It is sexually dimorphic; adult ...

, with a bordure added as a mark of difference.

The Prince of Wales's feathers

The Prince of Wales's feathers is the heraldic badge of the Prince of Wales, during the use of the title by the English and later British monarchy. It consists of three white ostrich feathers emerging from a gold coronet. A ribbon below the corone ...

, often adopted as insignia by members of the college, appear as decorative elements within the college buildings and appear on the official college tie. It probably represents Edward, the Black Prince

Edward of Woodstock, known to history as the Black Prince (15 June 1330 – 8 June 1376), was the eldest son of King Edward III of England, and the heir apparent to the English throne. He died before his father and so his son, Richard II, su ...

, Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales ( cy, Tywysog Cymru, ; la, Princeps Cambriae/Walliae) is a title traditionally given to the heir apparent to the English and later British throne. Prior to the conquest by Edward I in the 13th century, it was used by the rulers ...

, who first adopted the device, the senior grandson of King Edward II, although it may represent King Charles I, who was Prince of Wales